The following is reprinted (with permission) from the Spring 2019 edition of the Myosotis Messenger - the bi-annual newsletter of the Edmund Niles Huyck Preserve, a lovely tucked-away protected area in upstate New York with a long history as one of the oldest biological research stations in the U.S. The preserve also offers some research grants - one of which was awarded to Scott LaPoint and myself for a camera-trapping and snow-tracking study. This short essay was written as the outreach component of receiving that grant.1

waterfalls

When I first set foot in the Edmund Niles Huyck Preserve (or, more precisely, set ski) it is on a clear day in February after several days of steady snowfall. There’s nothing quite like being on new snow on a new day in a new place, the quiet of the forest brushed only by the swoosh of the skis, the never-quite-knowing what comes after the next curve.

After a steep and woolly ascent along the waterfall and some bobbing through hardwoods, I find myself cutting across Lake Myosotis towards yellow cattail stems poking through the ice on the northern shore. Near the bank, my ski suddenly sticks, and – after a brief moment – I feel cold fingers of water tickling my ankles. Trying to steady myself, I topple. Now my gloved hand is firmly shaking hands with the water below. This,the north end of the lake, is where the feeder creek flows in to the lake, and it hasn’t frozen quite as solidly as the rest.

It is at that moment – awkwardly splayed and mainly immobile – that I glance up into the trees and lock eyes with a coyote. Larger than any I’ve seen before, its mane is broad, its coat is thick – a pale grey blended with tan – its ears are turned forward, its body more still than the trees.

And, as my twisting self-extraction out of the sludge turns into a no-less desperate dance to ready and aim my camera, the coyote swivels and lopes, easily, straight up the steep snowed-in bank. The shutter clicks at nothing but trees.

hemlock stand (photo by Scott)

Now two years later, I am back in the Huyck Preserve, setting out with my friend Dr. Scott LaPoint (an expert in the mesopredator fauna of New York State) and Dr. Anne Rhodes (an expert in everything Huyck Preserve) from the sturdy old research center on Lincoln Pond to find a suitable site for a winter field study.

Our plan is to find a patch of woods, strap 54 cameras onto trees in a dense grid, track animals in the snow, match the tracks to photos, and learn what we can about the coyotes and the fishers and the foxes (and if they don’t show up, about the squirrels and the deer). But between the lines of our scientific plan is a simple, selfish, desire to tromp around the woods in winter. If we cross tracks with my old friend the coyote, so much the better.

There are no deep drifts this bright mid-December morning, just a dusting of snow. The Preserve is like overly powdered sugar donut in a glowing display case, the dusting slowly crusting and fading in the bright sun.

Even still, the snow has stories to tell.

Here, for example, along the creek by a bridge, an otter struts along the bank, betrayed by the wide splay of its feet,the furrow of its tail, and the eventual belly slide into an exposed riffle. Along the wood railing of that bridge, the tidy tracks of several mice (deer mice? white-footed mice?): tiny clusters of feet, each foot a cluster of four round-looking toes. Just below, the small, close predatory steps of a weasel (short-tailed? long-tailed?), entering the rushes at the pond’s edge.

mouse

Nearby, a foot-wide boulder is covered with a tidy toupée of snow. In the middle of it four squirrel feet. The rear haunches wide, the front feet prim and forward. There are no tracks leading to it or away, just a birch creaking lightly in the breeze.

Tucked between remnants of three, centuries old, stone pasture walls, we find a stand of slender sugar maples. The area is flat, neatly delineated, open to sky and snowfall. The trees are almost uniform in their layout. A coyote (the coyote?) has been here recently, has sliced the field diagonally, northeast to southwest, straight as an arrow, not pausing to sniff or mark or tarry under the sky watching through the sparse and naked maples.

We have found our site.

Conditions are perfect for dragging stakes, tying bright pink ribbons to trunks, measuring distances between trees that will soon be strapped with cameras. The day is long and tiring and wholly satisfying. But by the time we are done, the snow is also very nearly gone. All the life in the forest that scurries and hops and saunters and trots and sniffs at this and snorts at that now leaves no imprint on the bare ground.

It feels tragic, somehow. As if a great civilization had lost the art of recording its own history.

In the sturdy old laboratory at the south end of the pond, we are camped on cots next to dusty sample cabinets of small mammal skulls, beetles and damselflies pinned to frames by ecological collectors past. At the end of a long day, we, at least, have not yet lost the ability to write. I jot down some preliminary “findings”:

Creatures – abundant. Snow – unreliable. Soon – the trees will be our eyes.

Outside, the night is dark and moonless and silent, except for the occasional shriek of a barred owl.

Post scriptum:

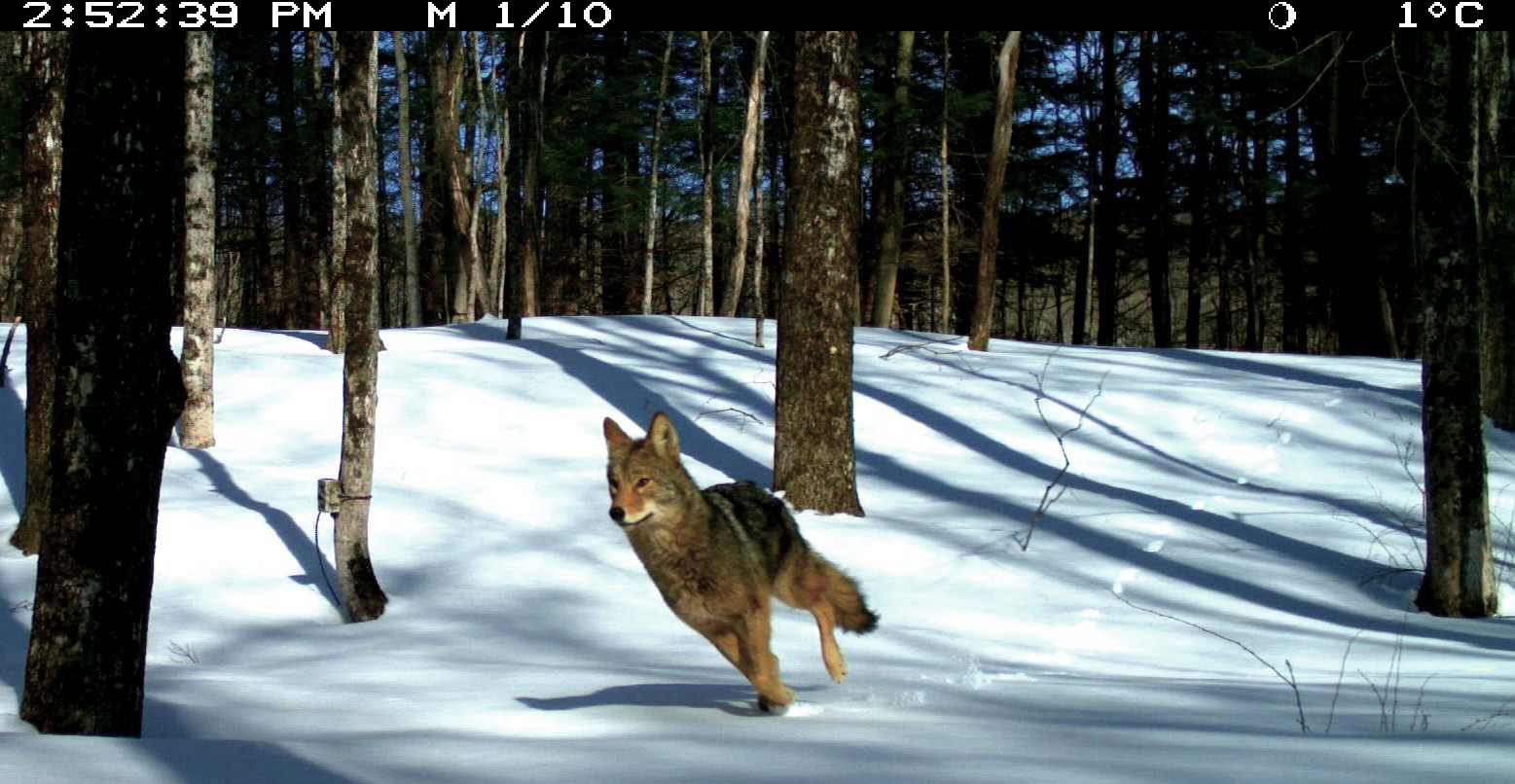

a camera “traps” a coyote

-

Another component of the grant, of course, is to actually analyze the results of our study. That bit, like so much else, is a work in progress - but might be the subject of a future post. ↩